- Home

- Yvonne Fein

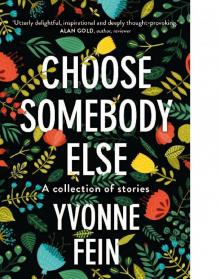

Choose Somebody Else Page 8

Choose Somebody Else Read online

Page 8

‘You have gained weight, Jacqueline, and it is not good. Do you think that just because he has married you, you are safe and can let yourself go? Become sloppy, lacklustre? It is not so Jacqueline. I know too well how easily a man is distracted from the boredom of what he knows by the lure of something quite other. Your man will surely be no different from the rest.’

This time silence would not serve.

‘It isn’t true,’ I said. ‘I’ve put on weight because I’m pregnant.’

For the next few months she was gentler though no less demanding. She was careful not to cut me with the blade of her sarcasm; and if I was slower or more clumsy than was my wont, she would only shake her head as she passed by me in her wanderings.

‘Foolish child to have a child.’

But as my time drew nearer and I became more cumbersome, her excitement heightened and her instructions for the care and exercise of my body increased and intensified. Her pleasure knew no bounds when, six weeks after the birth of my daughter, I returned to her class, softer, less able in body, although somehow firmer in my resolve to work.

‘It is good, Jacqueline; it is all right. You must not allow the frustration to overcome the will. Your body will once more obey you if you work. And I see that you want to. It is all right, Jacqueline.’

Yearly she would travel to Israel to visit her two sisters. The three of them must have been like a fractured Chekhov play in those hot, Tel Aviv summers. Yearly she would return after her two-month sojourn, to exhort us to work harder, to regale us with her experiences and to comment shrewdly on Arab-Israeli relations.

Yet each time she came back, regret and bitterness became more evident in her voice. Uprooted from her beloved Warsaw by persecution and prejudice, she had gone to live in Palestine, a land she came to hate for its harshness. The older she became, the more her resentment grew. Arriving in Australia she realised that it would always be a country in the wrong hemisphere—a place to which she would never belong. But her resentment was ambivalent, confusing. How could you hate Poland and love Warsaw? How could you speak of the culture of that city, of the brilliant life as a costume designer that had been yours among its refined and erudite people? Weren’t they the same people who had betrayed and killed you in zealous service to the conquering army? And how could you call Australia, and Melbourne in particular, a barren wasteland yet patronise its ballets and its operas, its concerts and its theatres? It was this wasteland, after all, that had given you a comfortable livelihood, sufficient to indulge such expensive habits.

One night I was the last to leave, my fingers already on the doorhandle.

‘Does it bore you when I talk about my travels?’ she asked, surprising me. She so rarely spoke to me unless it was as a reprimand.

‘Not at all. I like it very—–’

‘You might say that even if you didn’t.’

I was silent. She wouldn’t have held me back for just a casual word.

‘I’ve begun to think—–’ she said

The phone rang and her words skidded to a halt. I thought I would wait to see if she still wanted to talk to me after the call. At first her voice was quite soft but soon she spoke at a normal level and I couldn’t help but hear.

‘I can’t do it.’

She listened for a while. I saw her shake her head.

‘Son or no son,’ she said, ‘I just don’t have any more money for you.’

Son-or-no-son said more.

‘I know, I know,’ she sighed at last. ‘You think if I give you this money, it will change your life. It never has before, why should it now?’

Again she listened, but now her foot was tapping at great speed. Even though I could only see her back, I could tell that her irritation was rising.

‘It isn’t so,’ she said. ‘Even if you write this play, this meisterstück, produce and star in it, you’re not Shakespeare. In a week it will all be over and forgotten.’

There was silence at her end once more. Like his mother, the son did not know the meaning of surrender.

‘No!’ she said at last, finally raising her voice. ‘Trust me—one week and pfft! No one will remember you, no one will care. You exist for a moment and then you don’t. The curtain falls. That’s all. Our time runs out, our bodies run down and lending you all the money I have in the world can’t change that.’

She slammed down the phone and, sensing a presence behind her, spun around. She had completely forgotten I was there.

‘You shouldn’t have heard that,’ she said. ‘I never meant for you to hear such things.’ She paused for a moment.

‘But now that you have, I don’t know. Perhaps it is better that you hear it sooner rather than later.’

‘I don’t mind,’ I told her. ‘It’s your truth.’

She shook her head. ‘Not my truth, foolish child.’ She was at her most affectionate when she called me that. ‘The truth.’

Then, one grey, autumn afternoon, when she was sixty-eight or thereabouts, she climbed a ladder in her extensive library to retrieve an inaccessible volume on an obscure subject. She fell and injured her back. For weeks her voice was pain-wracked and soft but her criticisms more deadly.

‘Do not, Jacqueline, bring your fight with your husband into this room, into this particular exercise. It is a shoulder stand, a gradual, but demanding movement. A defining movement for your body. There cannot be anger in it yet I see anger in your entire body. I do not wish to see it. Suffer it privately.’

The years passed and of course she grew older, but that progress was incremental, difficult to discern. Her body adjusted to its injury—she fought it as she had always fought herself—and she triumphed. But, for some reason, her attacks on the Poles grew more acid, less rational. I almost did not hear them, so inured had I become to her voice when it offered anything but its instructions to my limbs. Occasionally, a particularly intense remark would register, floating momentarily above me and then drifting away. Others might protest or beg her to be more moderate, but I kept my own counsel, knowing any other course to be futile.

Occasionally, she would complain of the gradually returning pain to her back. She could no longer exercise it away. Watching her in her suffering, I wondered if it were possible that her stoicism might actually be waning. It seemed grossly unfair that her body, so long her servant, should now become her master. It was at least ten years since her fall from ladder and grace. How had she offended the God in whom she had no faith? Her goal had been to reach the biblical, the Mosaic, one hundred and twenty years—her eyes undimmed and her vigour unabated—but the capricious intervention of a power far stronger than she seemed to be working its dark magic to prevent it.

I calculated swiftly as, lying on my right side, I raised my left leg at a ninety-degree angle to my right and gripped my toes to straighten and stretch the muscles that allowed me ever-increasing mastery. I was thirty-four. Could she be seventy-nine? Was it possible that…

‘Where does your mind wander today, Jacqueline?’ she said, abruptly snapping off my deliberations. ‘This is a yoga class, not one of those modern workshops you doubtless attend. A workshop is where you talk of dreams and visions, no? But here we do not talk and we do not dream. For the duration of each of our sessions, I claim your mind as well as your body.’

Nunya joined our Wednesday evening classes—a roly-poly Jewish grandmother, a Holocaust survivor whose arthritic limbs demanded the succour she had been told only this class could offer.

One night, after we had been exposed to yet another tirade against the Poles, we were walking to our cars.

‘When she explodes like that she is being ridiculous,’ Nunya said to me. ‘They saved my life, those Poles. I escaped from Sobibor where ninety-seven members of my extended family died. I escaped at the last moment and some gentiles hid me and fed me and risked their own lives for the sake of a frightened Jewish child. I

couldn’t even speak their language; I spoke only Yiddish. She has no right to curse them. She was not there. She fled to Palestine. In time and with her whole family intact. I do not love the Poles. I know their faults. I know they helped destroy my people. But I cannot hate them all—not the way she does. They saved my life. I will tell her one day. Just that.’

‘You mustn’t,’ I said with incredulity at such folly. ‘You mustn’t say anything; not answer her, not defy her. It would be a terrible, useless thing. I know. I have known her from my childhood. Ignore what she says, please. It will pass.’

‘To come again.’

‘Then you must let it.’

‘I can’t,’ she said. ‘They saved my life.’

The lessons changed.

‘I cannot demonstrate the exercises today, ladies, merely instruct. My back does not permit me. This useless body. It betrays me like everyone, everything else in my life.’

Her spine, that strong supple lifeline was deteriorating. It gave her almost constant pain now and she was powerless before it. So, we strove to please her, even knowing that we strove towards the impossible.

‘Jacqueline, I see you have forgotten your socks today. Your feet are cold and the muscles tense. You dress children of your own, yet cannot dress yourself. Nunya, those socks you left here last week, may Jacqueline avail herself of their warmth this evening?’

‘But of course,’ said the woman, rolling onto her ample stomach to facilitate rising.

‘There’s no need,’ I protested weakly, bringing down retribution on a head already aching.

‘Silence please, Jacqueline. There has been too much disturbance in the class already without further demur on your part.’

Nunya beamed at me as she handed me the socks.

‘You look after these, young lady,’ she said softly. ‘I brought them back with me from Poland. The shop where I bought them stood there in my childhood exactly where it stands today.’

Whatever the condition of her spine there was still no sound our teacher’s ears could not catch.

‘If I had known they were Polish, I would have burnt them. There is no need to become mawkish over a pair of socks made by them. Everything they produce is tainted.’

‘That is not fair,’ said Nunya, moved finally and fatefully to confrontation. All of us were now lying on our stomachs in readiness for the next exercise. I found myself covering my head with my arms in much the same way as blitz victims must have tried to shield themselves from bombings.

‘It is not fair to hate them as you do. They saved my life. Without them I—and there are others like me—would not be alive today to listen to your talk.’

‘Without them, Nunya, the Germans could not have done their filthy work.’

‘But it was the Germans who did it, who started it, who thought of it all. Not the Poles.’

‘No, not the Poles who cheered as we died.’

‘As we died!’ Nunya’s indignation rose. ‘You weren’t there as we died. You were safely away. They killed my father, those Poles. I know what they are. I make them not into angels or saints. But I saw enough to know that not all of them are as evil as is your mind against them.’

‘If you can speak like that, you don’t know anything. They forced me out of the city of my birth to Palestine, a land so dry and so hostile that it made every dream of mine a nightmare. And this Australian desert was my only awakening.’

‘You talk of dreams! In the first eighteen years of my life I lost my family and everyone else who ever meant anything to me. But still I will never accept what you say.’

‘Enough now,’ she said, and I thought her voice sounded weary. ‘We must work. We have wasted enough time with this nonsense.’

Outrage spurted from Nunya. ‘Nonsense, you call it?’

‘Yes, nonsense. I will listen to no more of it. Be silent or leave.’

I could see that Nunya did not want to do either, but in the end she left the room, flinging only her coat over her costume. She slammed the front door and we could hear her car door slam, too. Moments later her engine roared and all we could do was lie there, stunned at the anger that had invaded our classroom.

We continued in a syncopated, unnatural rhythm, fraught with a tense fragility. When the final movement was executed, the other women departed at speed; only I remained behind, still seated on the floor. I was fixed in a groove worn thin by my movements over the years. I looked up to see bitter grief in eyes I knew almost better than my own.

‘What have I done?’ she asked.

‘Nothing,’ I said, ‘you’ve done nothing’.

‘Why did I have go on and on? Tell me, Jacqueline. In your silence you have always known things you were not prepared to share.’

‘You did it because you are who you are.’

That felt inadequate, but I could think of nothing else to say. We both stood up.

She came close, putting her arms around my waist. The top of her head nearly reached my breasts.

‘Why did I do it?’ she asked, another question for which I had no real answer.

I felt powerless in the face of her torment but at the same time an unfamiliar resentment began to stir in me. She was the teacher, after all—how could she be asking for my advice? All these years I had trusted her, deferred to her, complied with her every instruction. Her questions were a betrayal.

‘You must not cry, Jacqueline.’

I was forced to speech, my voice fierce. ‘I’m not crying. Why would I cry? You should be the one who cries. This madness will destroy you. You can’t continue like…like… an earthquake. Soon it will force out not just Nunya but all your students. Then what?’

I could have gone on, but she raised her hand. ‘Thank you. Your answer is sufficient, but in truth I should not have asked for it. I am eighty. You cannot become my teacher after all these years of having been taught by me. I never learnt to learn except those things I taught myself. I am too old to change even if I wanted to. And I do not. Go home now to your husband, your children.’

‘To leave you alone?’

‘It is what I have chosen.’

She was eighty-nine when she stopped teaching, ninety-five when she died. All of her Wednesday-night pupils stood together at her graveside and made a pact. We would gather at my house every week and practise the exercises she had taught us. For a while we managed it, but it was not too long before our energy dwindled. One by one the women dropped out of the group until only I remained, sitting on the floor in my living room, trying to remember the moves.

WEINTRAUB’S DISORDER

Yossl’s forefinger perforates the air close to Rosie Weintraub’s face.

‘The point is,’ he says, but the point is often peripheral. Although he speaks with a Yiddish accent so strong that it will forever brand him a foreigner, he uses the phrase often. He believes it makes him sound like a ‘netchural’.

He is a family friend as well as a supplier of zippers and yarns to her parents’ clothing factory. He besets Rosie at every opportunity.

‘For discussion with a university gradjet,’ he tells her. ‘Issues that shmatte manufacturers could never understand, in a language they will always smash up.’

Rosie is too polite to point out that smash might not be le mot juste.

He likes to say ‘objectively speaking’ a lot, and ‘nevertheless’; yet inexorably he returns to ‘the point is’. His bearing is august and his mood elevated when he says it. After all, he knows of no other migrants who can roll out expressions so smoothly.

‘If ever there was a lost generation,’ Yossl tells her now, ‘it’s yours. Objectively speaking, I know it is my generation who lost you. Some even say that all we managed to pass on to you is pain from the Camps. Nu? If we admit it, will it stop you from keeping the psychiatrists and the Family Law courts in business? You’re lost and sick.

Blame us? Sure. But the point is, you’re the ones who are sticked—stuck—with it.’

With an eye to escape, Rosie mutters a few ineffectual niceties about a pressing work schedule, but it is her father, entering with the bottle of vodka and two glasses, who rescues her.

‘Why she listens to you is a mystery,’ Abraham Weintraub booms, pinching Rosie’s cheek. ‘Lost and sick!’

‘Nevertheless,’ Yossl declares, ‘I make sense’.

‘You talk rubbish!’ Weintraub retorts as Rosie edges toward the door. ‘Look at her—a lawyer with Minter Ellison. Do you know where she’s going when she leaves here? To the airport, to pick up another lawyer—a professor! An American! They’re writing a book together on International Law that you would have to be born again to understand! He comes here to her—to Melbourne—this big legal maven from New York.’

Rosie inserts her key in the ignition. The point is, she says to herself—Yossl’s words like the sting of dry ice on an exposed nerve—the fucking point is that she was a teenager when it first began.

She is depressed. Not your ordinary, unremarkable, adolescent blues but the authentic article, the original garment. It has something to do with her heredity of melancholic grandmothers and alcoholic uncles with a predilection for smoking and gambling. These are her ancestors, long dead at the hands of an enemy more bitter than illness.

She is in her tenth year at school, not wanting to go out anywhere, let alone participate in the elaborate pre-mating rituals of her peers. She is not able to study, not even able to participate in class discussions any more. She also manages to fail every mid-year examination. Not your forty-nine per cent: this student could do better if she talked less and paid attention more; but your certified zeros: this student seems to have left every test paper blank.

The academic fiasco seems the most intolerable of her troubles, but it is all traumatic. To claim that one component of the ordeal is worse than another is, she feels, like having a preference for gassing over electrocution. Even so, it is a most serious complication for a student to fail everything at Mount Scopus Memorial College. They ask you to leave if you make a habit of it.

Choose Somebody Else

Choose Somebody Else