- Home

- Yvonne Fein

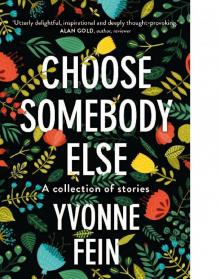

Choose Somebody Else

Choose Somebody Else Read online

BOAT PEOPLE

‘You were drunk,’ said Dean Harris.

Claire Gold closed her eyes.

At the annual Chisholm Address she had interrupted a lecture given by the renowned Professor Wright.

In advance, Claire had vehemently distrusted the relevance of his oration—attendance compulsory—to her studies. More-over, she was filled with contempt for any fool who could still find redemptive qualities in Stalin’s Russia, even—no, especially—if he hailed from Oxford. Having lost two great uncles, doctors both, in the purges of 1936, she could not bear listening to an apologist for a paranoid, psychopathic regime. So, knowing what the day held in store, she had charged herself with a breakfast of Coopers Pale Ale, washed down with four, or it may have been five, Extra Añejo tequila shots. Halfway through the discourse, she had risen to her feet, a diminutive loaf of bread powered by too much yeast. She had suggested to the great man that he had obviously neglected to consider Irving Berlin’s profound couplet on communism.

Professor Wright had inclined his head courteously, giving her the floor.

‘The world would not be in such a snarl,’ she’d said, ‘if Marx had been Groucho not Karl.’

Dean Harris recalled her to the present. ‘Why should your scholarship not be revoked?’

She felt hectic colour rising to her cheeks and knew her wild red hair would match it.

As always, she was embarrassed. Not everyone turned scarlet in extremis.

She shook her head. She wanted to write. That was all. Ever. And she was broke. News of the writing scholarship from Monash University almost made her believe in the efficacy of prayer, but it had come at a cost—the necessity of completing a Bachelor of Arts. Along with the writing components, her attention would be forced upon sociology, psychology, and postmodernism. These she considered to be among the most pissant subjects of academic inquiry, worse even than astrology. They were fit for investigation only by lunatics and layabouts.

‘If she’d lived, Hannah Arendt would be 110, today,’ Claire said, hating herself for not keeping quiet.

The dean was irritated. ‘I fail to see—’

‘I spent the night reading Eichmann in Jerusalem in her honour. And her notes on the banality of evil. In memory of my grandparents.’

‘Which is relevant to your personal situation, how?’

The blood so recently saturating Claire Gold’s face seemed to leave it with even greater alacrity. She sat silently, unwilling or unable to speak further. She was well aware that Dean Harris was an Australian Jew of Anglo-convict rather than Holocaust-survivor stock. Why, she did not know, but he had gifted her with that information at their very first interview, filling her with misgiving. She knew his type: loath to be reminded of his origins; losing all patience with what he saw as survivor self-dramatisation. She hated the fact that he could so carelessly cheapen the valour of those who had outlasted the Thousand Year Reich.

What should she, could she, do as the offspring of first and second-generation survivors? They had bequeathed her a legacy which forever cursed her to cling to a tradition of persecution. Look at bloody Harris; neither Jew nor Christian would ever guess at his ethnicity. His must be a far easier way to navigate the rapids of being a Jew.

And now when she needed them, no words came.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘You can’t, or won’t, explain it to me, but perhaps you could write it. That’s why you’re here, isn’t it? To write. Not drink. I’ll give you 48 hours. If your words pass muster, I will speak to the board on your behalf. If I find them wanting…’ He left the sentence hanging.

‘I might need more time.’

The dean smiled—more a grimace, really.

‘How much?’

‘Four days, five?’

‘If you think it will help.’

She saw he didn’t really care, and without warning, she shivered.

According to my mother (Claire wrote), my grandparents met across barbed wire. My grandfather risked both their lives when he’d achieved serendipitous access to a loaf of bread. All he could think to do with the treasure was to give some to his one, surviving brother and throw the rest over the electrified Jew-proof fence into the hands of the 17-year-old, Jewish-Hungarian princess, who would become the love of his life, the bane of it.

So he threw the bread. She caught it and was caught with it. A kapo—a Jew, a lowly fellow prisoner, who hated my grandmother’s haughty insistence on cleanliness—slapped her face and reported her to the camp commander who came into the women’s barracks that very day, his gun loosely holstered, to find her sweeping the floor.

He watched her for a while. Hungarian Jews came to the camps in 1944, late in the war, relatively well-fed, untraumatised. And Hungarian women had a reputation for beauty. The kapo watched the camp commander watching her. He took her hands in his as, startled, she allowed the broom to clatter to the floor.

He gazed at her palms, their improbable softness, their whiteness, their clean smoothness.

‘Fräulein, I see these hands have not had much to do with brooms.’

Fluent in many languages she looked at him, green-eyed, willing the fear out of her voice and even out of her bloodstream so he shouldn’t feel its tremor through her fingers. He might as soon shoot her as hold her hands for the crime of catching bread.

‘Perhaps not with brooms, sir,’ she said in German. ‘But with other things, these hands are gifted indeed.’

He forgot about the bread and the wire. That was surely her intention. He forgot to ask who threw it. That, even more so. He took her away from the broom to a room where the kapo could not watch and where questions asked with words had no purchase.

What did my grandmother think about, I often wondered, when for weeks every year my grandfather left her in the hands of psychiatrists and hospitals? When the wires were tripped, when they frayed and snapped in spasms of remembering? I had no way of knowing, but suspected that Australian-born victims of bi-polar disease weren’t plagued by recollections of Josef Mengele pushing them to the right and their mothers, clutching their baby brothers, to the left, to the gas, where the only way out was up.

That story, about her grandmother and the camp commander, was catapulted into Claire’s teenage consciousness by an Israeli cousin whose grandfather was her grandmother’s half-brother. It belied the notion that there were no gossips within, and later without, the camps, daring to judge the morality of another survivor’s actions. Claire always felt proud that her grandmother had chosen the slight chance of life over death. It was her daughter Amy, and granddaughter Claire, she had chosen, even though she couldn’t have known it then.

Claire pondered, her fingers trembling above the keys. Her mother had treated her only with kindness. No discipline, no harsh words. As though compensating for her own parents’ harsh, pre-Holocaust rearing.

‘Darling, the teacher rang:

‘You talk too much in class;

‘You haven’t handed in your last two assignments;

‘Your locker is always untidy;

‘You never remember your gym shoes.

‘What do you think we should do?’

Claire wondered if her mother thought that the simple act of reminding her would cure what ailed her, but it never did. Much of the time Claire simply thought, so what! Grandmother Ruth’s memories or Grandfather Ezekiel’s stories rendered so much of her life irrelevant by comparison.

Now, as she tried to write things down, wasn’t she simply turning excruciating truths into stories—stories, for God’s sake—to make them palatable for the dean? She was sickened by the thought.

When I was only fifteen (Claire wrote) I remember saying to my mother, ‘Now I know I can trust you’.

‘Because?’ she asked.

‘Because you told me the truth and now I know what to expect,’ I said.

Although she was already drowsy, under the influence of a pre-anaesthesia agent prior to cancer surgery, I still couldn’t stop myself from asking her: ‘Why you?’

‘That’s my question, sweetheart,’ my mother replied. ‘Why me? But I already know the answer. A gift to Ashkenazi Jews—like Hitler and death camps were to your grandparents’ generation. It’s the BRCA1 gene. I have it. No bosom is sacred. I have instructed the doctor to excise it.’

I meant to say to her, your bosom is sacred, but what came out was, ‘Does that mean I have the gene, too?’

Nearly a decade later, in the wake of the Columbine High School massacre, my mother turned away from the television and sat in uncharacteristic silence until I asked her what she was thinking.

‘Gun control,’ she said. ‘This disaster wouldn’t have happened if there had been proper gun control.’

I waited.

‘But,’ she said, ‘do you think that if every Jewish family had had one gun, only one, that they could have rounded us all up like that?’ She said ‘us’, even though she and I had been born after the fact.

As Claire walked the streets of Carlton, remembering, she thought it was not fair that the dean’s words could exist alongside the mild temperatures and pale blue skies of a Melbourne spring. There should have been black clouds, lacerating rain and southerly gales. Instead, bright flowers against old stone buildings dazzled her—daffodils with their golden trumpets; coral and black oriental poppies; snowdrops and lavender, sweet williams, crocuses and primroses. The drought had so recently broken that she thought she could never tire of gazing at them, breathing in their scent. She had almost forgotten what it was like to live in the midst of colour and fragrance.

Jimmy Watson’s is a bar and restaurant in Carlton, close to the university. She waitressed there on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights and had become friendly with another waiter, an Irish backpacker heading off soon to explore the communes in New South Wales. Claire wished she could follow him. She would be safe with him. He seemed always to know exactly where he was.

He laughed. ‘I have to go before my visa runs out,’ he said. ‘You can go any time. Why wouldn’t you?’

‘I have this phobia.’

He actually took a step back.

‘I’m always afraid I’ll get lost,’ she said. ‘Even in the city. I can get disoriented in a minute. And GPS doesn’t always help.’

‘That’s a bit weird.’

‘It’s very weird. I worry I might never find my way home.’

She didn’t know why she had confided that. It had always been something she thought she needed to conceal. She certainly didn’t want to explain that many of her ancestors had been forced from their homes in 1941, so that even after four years had passed and it was all supposedly over, they had never been able to make their way home again. On the property they had appropriated, their erstwhile neighbours were waiting to kill them if they tried to recover their homes, their land and their belongings…

Her assignment lay heavy. She still had to find more words. Where?

So many years ago, drowsy, waiting for the surgeon, Claire’s mother had talked and talked. Her stories had seared themselves into Claire’s consciousness. The dean didn’t deserve them, but she knew she would give them to him anyway. As she prepared to write, she conjured up her mother’s words. They seemed to fly straight from her remembering mind to her fingertips where the keyboard caught them.

In Yiddish there is a saying: Shver tsu zeyn a yid—It is difficult to be a Jew. My mother learnt it at her father’s knee, before he pulled that knee out from under her.

My maternal grandparents were on the right side of the world at last, having escaped the maw of Auschwitz, having met there, in fact, and fallen in love—fallen in something, leastways—and married once the insanity was over. Not that they ever escaped it. You don’t inhabit such madness without carrying it with you for the rest of your life. You pass it on, this deformed inheritance, to generations which come after so that they never forget the culture of survival and victimhood.

But a culture of mercantilism was also passed on. The baggage my kin schlepped from one side of the world to another contained much more than psychosis and affliction. Two overlocker sewing machines accompanied my grandparents on their six-week boat trip across the Indian Ocean, which made me the grandchild not just of survivors but of some of the early boat people.

I’ve heard it said that all white Australians—to extrapolate, all humanity—were boat people of one stripe or another. Stripes, stars… not flags and freedom, but the yellow Star of David emblazoned upon the vermin-ridden, grey-and-white striped pyjamas in which the Nazis clad their concentration camp inmates. I was the grandchild of that sort of boat couple.

Claire knew that her grandparents and their ilk were called New Australians. Even now, when they would have been quite old Australians, they would still be New. They died never having been to a football match nor having eaten a meat pie. Paul Hogan and Kylie Minogue passed them by, although they took her mother to see Danny Kaye as well as the Mickey Mouse Club. They also made sure she was part of an audience that witnessed Dame Margot Fonteyn in glorious flight with Rudolph Nureyev.

Doing all that, they were convinced, was the best way of giving their daughter a truly Australian childhood. It certainly wasn’t an Eastern European, Orthodox Jewish childhood. They never agreed on much but were unanimous in refusing to replicate the small-town, narrow-minded theocratic fascism which had blighted both their childhoods before the real fascists arrived.

In the Lodz Ghetto, in Auschwitz and in the labour camp named Goerlitz, they called my grandfather, ‘My Lord’. He was tall for a Jew—almost six feet—and handsome in the way of Gregory Peck, women would tell him, often shamelessly, in his young daughter’s presence. He was brave, too, I was told by those who had known him, and I had no reason to doubt them. He became the valet of a camp commander and stole food intended for the German Shepherds to divide among those from his shtetl and, of course, for his wife-to-be.

Repressed anger and a sense of powerlessness would plague him the rest of his life. He relived the images of his little brothers being taken from him, disappearing like Hansel and Gretel into the Grimm Teutonic ovens.

Ezekiel, what is it? Ruth would ask him as he woke in the night, crying out with dreams of flight and pursuit. But who really knew what he dreamed, what he remembered? Those stories he never told.

I know that my mother never did discover the catalyst for my grandparents’ decision to cede guardianship over her. She never asked—that was her strategy for staying sane—and no one ever said, which was theirs. She told me that she was dropped off at her uncle’s seaside home—not for the first time, so she wasn’t afraid—and that she would be picked up in a couple of days. Which stretched into weeks, months. She was nine. Sometimes her parents came back as abruptly as they had left—such hugging and crying—only to leave again.

The last time, she remembered, her mother exchanged a glance with her father saying, ‘We should go out in the boat, just the three of us’.

‘We should,’ he agreed.

‘Sophie,’ he said to Amy’s aunt, ‘when was the last time you used it? Is it in good working order? Should we give it a test run before we take the child out?’

Sophie shrugged. The ways of her mad brother-in-law and even madder sister were a mystery.

‘We haven’t used that boat since you were last here,’ she replied.

‘Then,’ said Ruth, ‘let’s you and I take it out for a little spin. Just you and I, Ezekiel.’ Ezekiel smiled and agreed, and my mother said they both embraced her quite

fiercely. She wondered whether hugs were supposed to hurt like that. And they waved to her for a long time on the sun-dappled water until they drifted out of sight beyond the inlet.

The stories had become a weight my grandmother could not bear. It was no longer enough to share them with my grandfather. It was a given that he would hold her fast. To hear him tell it, he had been born—no, destined—to offer her succour. But telling him her troubles had become like telling them to herself. There was no catharsis. So when they took that little boat out, their daughter watched them from the shore. She saw her father turn around, giving her his last glance before asking Ruth which direction she wanted to take.

Once upon a time, the kabbalists said, God was so lonely that he withdrew the boundlessness of his presence, which occupied the totality of the universe, in order to make room for the world to be formed. It broke him. The enormity of his withdrawal, mingled with the enormity of his passion to create something beyond his own infinitude, shattered the Divine Oneness, causing the sparks of his immortal light to be flung to all extremities of the Earth. And from that time until the present it has become humanity’s sacred charge to find and gather every one of those sparks, returning them to the Presence so he and his creation might again be whole.

Surely sparks flew through the air as my grandfather flung his love over that wire. And, as it landed in hands not bred for sweeping, were not these flashes of light stored in those very hands for the Holy One’s redemption? Yet in considering the process of their emigration—whence they left nothing behind and did not know towards what they were sailing—I lost sight of what their stories made them out to be. I lost sight of what I had not been alive to see and yet to which I was obliged to bear witness. Now I could only imagine the covetous darkness that must have drawn around them as they and their little vessel—just you and I, Ezekiel—sank.

Did they hold each other’s hands? Stupid question. They held hands even as they slept. Once in a lucid dream my mother said she reproached them: ‘You shouldn’t have left me.’

‘We had to,’ my grandmother replied in the dream. ‘You weren’t enough. It’s not your fault. No one could have blocked out what we saw. Certainly not a single child.’

Choose Somebody Else

Choose Somebody Else