- Home

- Yvonne Fein

Choose Somebody Else Page 3

Choose Somebody Else Read online

Page 3

Within moments of her ascending the ladder she was descending. With one hand she held onto its metal side for balance; with the other she clasped my grandmother’s rosewood box to her chest. Wordlessly she placed it on the long Formica bench top.

‘Where did you get this?’ she demanded. ‘There was only ever supposed to be one.’

‘There is only one. It belonged to my grandmother, may she learn Torah at God’s table in the World to Come. She gave it to me just before she died.’

Adminah opened it to the light. At once a fragrance, delicate yet powerfully familiar, seemed to suffuse the room in a vapour of lavender oil, milk of magnesia, Marlboro Lights and the faint tang of crisply fried onions. She closed her eyes and breathed its fragrance.

‘I know it,’ she said. ‘It’s an essence.’

‘What do you mean?’

But she shook her head. Then, with quick fingers, she flicked through the first few papers, becoming gentler as she recognised their fragility.

‘They’re the recipes,’ she said, flicking a little faster. ‘They’re still here. All of them. Some in Hebrew, in English—and look, these ones are in French. They’re more recent, and my God, is this Ladino? That never used to be there. And there’s German, Hungarian. Nathan, do you appreciate the value of this? Have you ever looked inside?’

Her voice had taken on a breathless quality and not all of her words seemed to be making sense, but her questions had taken me back to that rain-lit Sabbath night which had ended with my grandmother’s dying. I had come home, juggling the walking stick and the box. I had put them both away, not remembering them until taking on my new job. Then I had moved all my belongings into the little flat at the back of the Yeshiva’s garden. Still I didn’t have the heart to examine that rosewood chest. So, I stored it in the Yeshiva’s huge kitchen, on a high shelf, where I could forget about it.

‘No way she gave it to you to hide away.’ Adminah said. ‘She gave it to you for a reason.’

‘What reason?’

‘I’ve never known that. Perhaps the answer might lie in the cooking. Tomorrow night instead of lamb we can have…’ She reached into the box, pulling out a card at random. ‘Red lentil stew to be served with crusty rye bread: Genesis, 25:29-34. Why does it say that?’

‘It’s Jacob and Esau,’ I said, matching the puzzlement in her eyes with my own. ‘The deal over the birthright in exchange for the stew. What else does it say?’

Adminah skimmed the closely written Hebrew letters. ‘Just ingredients, quantities, method of combining, cooking time. And apparently it serves 18.’ She looked up at me. ‘How many are we expecting tomorrow night for the Rav’s birthday? Wouldn’t he have invited a few extra?’

‘Eighteen,’ I replied. ‘The rabbi is expecting eighteen.’

I noticed there was writing on the other side of the card. As I took it from her hand I heard a gust of wind spring up outside. It blew through the old oak trees behind the kitchen garden as the sky darkened into twilight. A vicious squall beat itself out against the window panes and I thought I could hear currents of air coiling themselves through the ancient branches. Someone knocked, and I thrust my head into the hallway. A fragile outline, incandescent in a pale red dress, hovered beneath a row of flickering light bulbs all, improbably, about to expire at once. She turned toward me and, as though she were a mirror, reflected my face back at me. Her own features seemed to be obscured by the silvered glass whose glint I could have shattered with a thrust of my fist.

‘What is it, Nathan?’ Adminah stood on tiptoes and looked over my shoulder.

At the sound of her voice the shade disappeared. I shook my head to clear it. ‘Nothing,’ I said turning around, trying to stifle the alarm rising inside me. Adminah’s face had paled.

We sat down at the table, neither of us willing to canvass what might or might not have just happened. I flipped the recipe card over. The first word was ‘Commentary’ in Hebrew and next to each ingredient were lines of the tiniest writing.

COMMENTARY

Red lentil stew (with crusty rye bread)

CEREMONIES

Birthdays and birthrights

INGREDIENTS

Lentils: red for the blood in bloodlines that crossed and cursed and may one day reunite

Butternut squash: gold for the wealth of generations

New potatoes: white for the death of the dream of Jacob

Carrots: for the orange sun that ripens them

Parsnips: for the cream that smooths away sorrow

Onion: for the tears of Rachel

Tomatoes: sear and sear again for the smoke of sacrifice

Salt, curry, white pepper, crushed red pepper: if even one is omitted, the journey halts

Garlic cloves: only if all are included is return possible

Coriander: roughly chopped for the green of springtime and rebirth

Vegetable stock: without which all fails

PREPARATION

Sauté onions and garlic slowly in an oil-heated pan until transparent. Add all vegetables to pan except for lentils, turning the heat up. Stir till vegetables are a golden colour. Add curry, stock and increase heat till ingredients are boiling in it. Add lentils, cover pan and simmer for at least 20 minutes. This will achieve tenderness of vegetables and legumes and thicken the sauce. Stir in coriander and swirl yoghurt over the surface. Serve on a bed of basmati rice, or with potatoes mashed in almond milk and butter.

Crusty bread on the side.

But the abnormal gave way to the normal. That night I served the young students, the rabbi and his wife an ivory soup comprising Daikon radish, peeled russet potatoes, cauliflower, wild mushrooms, Cipollini onions and silver-skin garlic. All were blended into a smooth puree with sea salt and coriander. I followed this with tender brisket, whose thin layer of fat on top had crisped to a fine, honeyed parallelogram. It was accompanied by stir-fried snow peas which snapped sharply between the teeth; herbed and roasted sweet potatoes and soft-on-the-inside, crunchy-on-the-outside shoestring fries. Dessert was simply a platter of melons and berries.

Adminah was rostered on to help me with the clearing and washing up. If I didn’t think too much about those strange little disturbances which seemed to be entwining themselves into some of our exchanges I could admit I was beginning to like her. She was lively, with a ready laugh and deep, green eyes that spoke volumes, especially when she was silent. I didn’t mind at all that she came by to flirt with me, even though I was a Rav, a rabbi. I liked the way her slender neck moved as she tossed back the curls that gleamed under the kitchen’s fluorescent lights. I thought it might be nice to go for a walk with her or take her out for coffee, but I also thought I might have to ask the rabbi’s permission. For some reason that held me back. I was embarrassed by the seven-year age gap between us. I didn’t want the rabbi or his wife to think I was preying on her innocence.

Just as she was giving the surfaces a final wipe-down Adminah asked me, ‘So are you going to make the red lentil stew for the Rav’s birthday?’

I nodded. ‘But I don’t know whether to serve it with a crusty rye or the mashed potatoes with almond milk and butter.’

‘Both,’ she said. ‘Do you need me for anything else?’

I shook my head. ‘I’ll see you in the morning.’ And I turned my back on her, wanting her to stay, willing her to leave.

I felt her hesitation match mine, but eventually she said, ‘Goodnight, Nachman,’ her voice on my Yiddish name a caress.

Before I started preparing crockery and cutlery for the following morning’s meal, I sat down at the table and rested my head on my arms. I dozed off briefly, my sleep light. Through it I heard rain begin to pelt down on the roof again. It turned to hail, striking the windows in splintering gusts. Still I did not raise my head. I should have. I should have risen from that table right then and fled to my bed in

my own little house all the way down at the back of the Yeshiva. But I didn’t, so when it came, I couldn’t help but hear it. Much later I would wonder where my grandmother had been on this night and on others like it. Had she hidden her face from me? Stopped looking down?

I was woken by a sound of tapping. Whoever was doing it had found the outside door to the kitchen, probably led there by the only light still burning on the grounds. There was a wilful perversity to the incessant sound. Tap, tap, tap: I will not cease, tap, tap, tap, till you open this door. Tap, tap, tap.

Not hammering, not thumping, only tapping. Without pause.

I stood and wondered if I were brave enough or inquisitive enough to answer it. I looked at my watch. Who, with honourable intent, would come knocking at a Yeshiva door at two in the morning? My curiosity mitigated my saner instincts. The rain was still coming down as though God had forgotten His promise never again to cause a flood.

In the entrance, beneath the harsh brightness cast by the coruscating tubes of light, stood a young woman. She looked no older than twenty. Her short white dress clung to her, soaking and transparent. On her feet she wore long, dark red boots which came up to her knees, and she clutched a duffel bag. It, too, had borne the brunt of the rain. She flicked her long red hair over her shoulders and it was wet enough to make a slapping sound as it hit her back. In her soft grey eyes, I thought I saw supplication, but in the face of my bemused expression, they became hard, slate cracking under ice. Her red, woollen scarf was wound around her neck and dripped rainwater onto the floor.

‘Are you lost?’ I asked.

‘I’m here, aren’t I?’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘I think you do.’

Her words were an echo of my grandmother’s, but I knew as much now as I had then.

She shrugged as if to say, we can leave this for another day and asked instead, ‘Is this the Soul of Fire synagogue?’

‘No, it’s Song of Spring. Didn’t you see the sign out the front?’

‘What sign? I didn’t see any sign. And anyway, there are so many synagogues around here that after a while there’s not much to choose between them.’

I sighed. ‘Soul of Fire is about two kilometres north of here. Near the tram terminus.’

Her shoulders sagged and outside the rain seemed to increase its force.

‘I can’t go back out there and walk another two kilometres,’ she said.

There were any number of choices I could have made at that point: I could have called her a cab; given her a lift in my car; I could have called Soul of Fire and told them of the foundling’s predicament; or even have woken the Rav to ask his advice. But I didn’t do any of those things.

‘Come in,’ I said. ‘I’ll find you some dry clothes and put your wet things in the dryer.’

I rummaged around in the charity box and returned with a skirt, a fleecy lined sweatshirt, fluffy socks and even a pair of slippers that looked as though they might fit. I gave her a towel and I pointed to the alcove where she could change in private. She closed the door and I stood outside it. I wondered what would happen if I opened it.

Before I could turn away she emerged. Seeing me standing there she gave a knowing smile.

‘I thought rabbis weren’t supposed to—’

‘Supposed to what?’ I asked before she could finish. My voice was hoarse.

‘You know what,’ she replied. ‘But I’ve never minded, never judged you.’

She looked tousled from having towel-dried her hair and she handed me her dripping garments. I made my way swiftly to the laundry, shoved everything into the dryer, boots, duffel bag and all, and half-jogged back to the kitchen. For some reason I didn’t like the idea of her being there alone.

When I returned she was holding the rosewood box with one hand and flipping carelessly through the recipes with the other.

‘Leave that! It’s not for you to touch.’ My voice sounded strange to me, abrasive. ‘I will wake you in the morning and drive you to Soul of Fire.’

She tossed her hair again. It was a lazy movement, seductive. Her thick curls, auburn and shot through with arrows of gold, were almost dry now. I had an urge to run my fingers through them, but she smiled and said, ‘Really, rabbi?’ Then she asked, ‘My things?’

‘Will be dry before we leave.’

Once more the light bulbs in the ceiling began to gutter, like candles running out of wax. She turned her back on me and, with her feet barely touching the ground, seemed to float into the alcove and lie shimmering above the covers. Her incandescence was too familiar. Now she became like a diamond-shaped mirror, reflecting everything above and beneath her. Again, a violent thought visited: if only I dared push her hard against the wall, against any surface, she might easily fragment—glass ablaze or moon eclipsed. But gone. I shut her door too loudly.

In the morning, the room, the bed, were empty and the clothes I had given her were strewn on the carpet. She must have found her belongings on her own. When I entered the kitchen Adminah was there, on her knees. I saw that the box had been knocked to the floor. It lay collapsed on its side, chipped from its fall, its contents scattered all over. Adminah had picked it up, the rosewood lustrous in her hands, and was trying to restore order to all those fragile instructions.

‘Who would do this?’ she asked. ‘Were we robbed?’

‘There’s nothing of value to take.’

‘Perhaps whoever it was wanted these.’ Adminah pointed to the floor where the recipes were scattered like leaves. ‘Perhaps I disturbed them and they fled.’

I didn’t want to think about last night’s visitor. From the window I could see that the sky was pale blue and last night’s rain still glittered on the grass. I thought I heard Adminah whisper, I know who did this, but I couldn’t be sure and then, her voice cool and unruffled, seemed to flow through me. ‘Red lentil stew,’ she said, brushing her fingertips carefully over the paper with its filaments of ink, so that I knew tonight I would be cooking for her, for the Rav and his guests, for my grandmother and those twin boys from long ago—Jacob and Esau. This time there would be enough for the two of them, for all of us.

Between two and three-thirty every day excepting the Sabbath, the Rav made himself available to his students and to the general public. In his study he would answer any questions that might have arisen for them. Because word of his wisdom and exceptional acumen had spread, an audience with him had become much sought after.

I was first in line to see him when he opened his door that day. He was a tall, watchful man, clean-shaven—which was unusual—with dark, knife-like eyes that could, and often did, puncture falsehood.

‘Well?’ he said when I had seated myself. ‘One rabbi to another. Is there really anything I can tell you?’

‘It’s about Adminah,’ I replied. Without warning my voice had taken on a husky timbre that made my statement sound like an obscene phone call.

When I didn’t continue, the Rav asked, ‘What about her?’

‘We’ve been spending time together and I was wondering if I could, or should, or maybe’—I stumbled over my words—‘maybe we could walk together or have coffee. I’m not really—’

‘Why are you asking me? Shouldn’t you be asking her?’

‘I thought it might not be the right thing to do. There’s the matter of the seven-year age difference. It makes me uncomfortable.’

‘There are seven years between my wife and me. It hasn’t been a problem.’

‘I don’t want to marry her.’

‘Really?’ he asked. His manner had become quite gentle. ‘Take her out, by all means. Time will tell. But that’s not the only reason you came to see me today.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You had a visitor last night.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I know. And you did well

to help her.’

Now he looked directly at me and quoted:

Cease to do evil,

Learn to do good.

Devote yourselves to justice,

Aid the wronged,

Uphold the rights of the orphan;

Defend the cause of the widow.

‘That’s Isaiah 1:17, 18,’ he concluded, ‘though I would hope you recognised it.’

‘How do we know that she’s among the wronged?’ I asked. ‘And I’d have thought she’s not old enough to be a widow.’

‘A young woman turns up soaking and destitute on your doorstep after midnight and you don’t think that somewhere along her journey she has been wronged? And yes, she might not appear to be a widow but who knows? Who knows where life has taken her? Equally, an orphan. No one to turn to but strangers?’

I could not understand how he might know those details.

‘It was quite strange,’ I told him. ‘She left without a word, a note. Should I perhaps go to Soul of Fire?’ I wondered why I would even think it. She had tried to destroy my grandmother’s box and—

‘Absolutely not,’ said the Rav, interrupting my thoughts. ‘You’ve played your part in her little drama and it was quite enough. I see you, Nathan. I see you a great deal more clearly that your grandmother ever did, though her eyes were not quite closed to you either. I know you have been to places no rabbi should go. And have done things there of which it is better not to speak.’

‘I don’t remember.’

‘You’ll remember when you need to.’

My blood hammered and one thousand tiny barbs bristled through my body. How was it that everyone, possibly even Adminah, assumed I had once attached myself to some perilous evil, and that now I needed to beware of doing so again?

‘So, take Adminah out for coffee,’ the Rav was saying. ‘Cook something new. And please neglect to think about the orphan. Her life and yours intertwined for a moment in time but that was enough—if not for her, then certainly for you.’

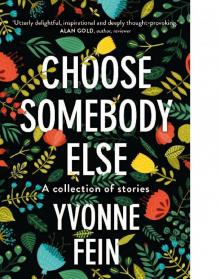

Choose Somebody Else

Choose Somebody Else